Golden Opportunity

There was a "moment of silence" before Saturday's Penn State football game. Symbolic moments of silence are a time-honored tradition at "American" sporting events, usually in remembrance of one or more people who have died.

There was a "moment of silence" before Saturday's Penn State football game. Symbolic moments of silence are a time-honored tradition at "American" sporting events, usually in remembrance of one or more people who have died.This time it was different. Officially the moment of silence was for child abuse victims. Nothing specific, just children who have been abused somewhere, some time. Not how they were abused, not where, not how many, and not when. It was almost as if the school and the fans just up and decided to have a moment of silence for victims of child abuse.

It wasn't very convincing. The real mourning was for Joe Paterno, Penn State's football coach since 1966. That was forty-five years ago. I was a senior in college in 1966. Paterno played college football when I was one year old.

It wasn't very convincing. The real mourning was for Joe Paterno, Penn State's football coach since 1966. That was forty-five years ago. I was a senior in college in 1966. Paterno played college football when I was one year old.During Paterno's tenure at Penn State he won 409 games, the most of any coach in NCAA history. He attained that distinction on October 29 of this year, defeating Illinois 10-7. The record had been held by legendary Grambling coach Eddie Robinson.

Now Joe Paterno has been fired, leaving Penn State in disgrace after public disclosure of his role in the child molestation scandal involving one of his former coaches, Jerry Sandusky. Paterno knew about the molestations, but by all appearances participated in a coverup of the crimes, along with the university president and other officials. It would appear that the record for most victories trumped all other considerations in Joe Paterno's mind - his advanced age (84), criminal activity under his trust, protection of children, the integrity of the football program, his own integrity.

Now Joe Paterno has been fired, leaving Penn State in disgrace after public disclosure of his role in the child molestation scandal involving one of his former coaches, Jerry Sandusky. Paterno knew about the molestations, but by all appearances participated in a coverup of the crimes, along with the university president and other officials. It would appear that the record for most victories trumped all other considerations in Joe Paterno's mind - his advanced age (84), criminal activity under his trust, protection of children, the integrity of the football program, his own integrity.Like virtually everyone else in the country I was surprised and shocked at the news. I shouldn't have been. I wasn't so enamored of Joe Paterno. It seemed to me he stayed far past the time he should have retired. When Penn State joined the Big 10 athletic conference I thought it was a craven move to win championships and make money for the football program, to the detriment of the other 10 teams. Of course, it was, but that's the nature of the game.

In pondering the whys and wherefors of the Paterno scandal I looked back on my own athletic experience for insight. For every Heisman Trophy winner or All-American there are millions of other athletes who play at the margins, unheralded and in most cases unknown. I was one of those athletes, far back in the pack. Still, I played, and learned much in the organized sports that I played so ignomineously.

When I was ten years old my family moved to Kankakee, Illinois. It was a baseball town, and in 1958 the Little League team played in the World Series finals. They lost to a team from Mexico that had sixteen-year-olds on the team.

When I was ten years old my family moved to Kankakee, Illinois. It was a baseball town, and in 1958 the Little League team played in the World Series finals. They lost to a team from Mexico that had sixteen-year-olds on the team. That same year I tried out for Pony League, the next level after Little League. I hadn't played in Little League, and in the tryouts faced fast pitching for the first time. The pitcher I faced, a guy named Jack Coy, was firing pitches at 90 miles per hour. In practice. What a waste. Major league scouts came to watch him pitch, but he later "threw out" his pitching arm, and didn't play baseball at all after Pony League.

That same year I tried out for Pony League, the next level after Little League. I hadn't played in Little League, and in the tryouts faced fast pitching for the first time. The pitcher I faced, a guy named Jack Coy, was firing pitches at 90 miles per hour. In practice. What a waste. Major league scouts came to watch him pitch, but he later "threw out" his pitching arm, and didn't play baseball at all after Pony League.The fast pitching scared the daylights out of me. I can still remember the sound of the pitches hitting the catcher's mitt. "Whop!" "Whop!" "Whop!" "Next batter!" I didn't make the cut.

The same thing happened the next year, without any batting practice. I wasn't a very good baseball player, and was smaller than most kids my age. When I was fourteen years old I was five feet tall and 85 pounds. I was pretty good for playing at the neighborhood park, but organized ball is on a different level.

Another thing stands out in my memory of going out for Pony League. During the mass tryout one of the coaches walked around, wearing his "Domestic Laundry" delivery driver's uniform, gripping a baseball the way pitchers do when they are breaking a ball in. He walked with swagger, and looked over the players like cattle at auction. Indeed, in the clipping at right the player assignments were referred to as an "auction," and players were "bought." I wonder what I went for.

Undeterred by this failure, I tried out for football when I started high school. I was the smallest kid on the team, but I was enjoying it, even though I was far back on what today would be called the "depth chart." My dad made me quit after about a month, telling me to devote myself to my studies, which I promptly stopped doing.

The following spring I went out for the track team, inspired by the great mile runner Roger Bannister. He was the first person to run a mile in less than four minutes, and I was inspired by his historic feat. I ran the mile at 4 minutes, 55 seconds in practice, and was put on the varsity track team, the only freshman on the team.

The following spring I went out for the track team, inspired by the great mile runner Roger Bannister. He was the first person to run a mile in less than four minutes, and I was inspired by his historic feat. I ran the mile at 4 minutes, 55 seconds in practice, and was put on the varsity track team, the only freshman on the team. Unfortunately, I never broke five minutes again, and got steadily worse every year. In my senior year I gave up running the mile and switched to the half-mile. I ran a good race my first time out, but again got steadily worse each race.

Unfortunately, I never broke five minutes again, and got steadily worse every year. In my senior year I gave up running the mile and switched to the half-mile. I ran a good race my first time out, but again got steadily worse each race.In my junior and senior years in high school I played football again, without distinction. It was fun, though, especially in practice, where I often played defensive back. I could pick out who was going to carry the ball by the ways players lined up, which angered the coaches. Finally one of them asked me how I knew, and I told him. I thought this would get me some playing time, but I think the coaches resented me figuring something out that they should have known. They were pretty crappy coaches.

They did give everyone a chance, I have to say. I was put in at halfback in games where we were winning handily, and one time at fullback, where I gained one yard before being piled on by the defensive line. I got the wind knocked out of me, and the coaches likely thought I was dead. The other team had a guy who weighed 270 pounds, and a couple of others who were about 220. I weighed 125. My one yard got into the season statistics, and was better than some.

They did give everyone a chance, I have to say. I was put in at halfback in games where we were winning handily, and one time at fullback, where I gained one yard before being piled on by the defensive line. I got the wind knocked out of me, and the coaches likely thought I was dead. The other team had a guy who weighed 270 pounds, and a couple of others who were about 220. I weighed 125. My one yard got into the season statistics, and was better than some.During my senior year in high school a friend organized a CYO (Catholic Youth Organization) basketball team, and invited me to play. He said we would probably end up in last place, but would have a lot of fun. That didn't sound like much fun to me, but I had an idea. I called a friend from the neighborhood, who was a star player on the public high school team that beat our team to win the regional tournament two years previous. He was six-foot-six, and was a fearsome talent, recently kicked off his college team for being a "gunner." He told me he would play if I paid his CYO membership fee, and I got the $11 from my dad, who believed he was paying for my membership. We won almost all our games, and would have won the championship had the officiating been honest. C'est la vie.

Strangely enough, basketball was probably my strongest sport. I went out for basketball when I was a high school freshman, and stayed on the team long enough to learn how to play defense - "Stay between your man and the basket" - and could jump pretty high. On the CYO team I was a good rebounder, and at five feet eight, played forward. I held the (then) highest scorer in the league scoreless, and we beat their team of public high school football stars by 28 points. It was the best team sport experience I ever had.

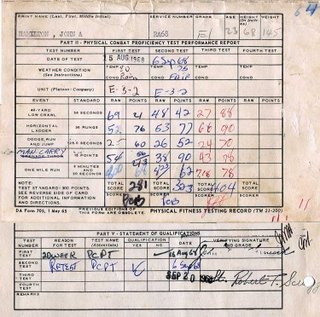

My greatest athletic performance was in Army basic training in 1968. Every few weeks we were given PT tests - physical training - to measure our progress in a number of tasks. I did pretty well in all of them, and surprised myself and the drill sergeants in "walking" the horizontal bars, where I maxed-out at 66. I think only one or two others in our company did better.

My greatest athletic performance was in Army basic training in 1968. Every few weeks we were given PT tests - physical training - to measure our progress in a number of tasks. I did pretty well in all of them, and surprised myself and the drill sergeants in "walking" the horizontal bars, where I maxed-out at 66. I think only one or two others in our company did better.One of the greatest lessons I learned in the various organized sports I played (or attempted to play) was to be wary of men who become coaches. I remember as far back as grade school that I felt an unease around coaches. There was something kind of off about them. A guy volunteered as our grade school track coach when I was about 12 or 13 years old, and he was an incongruity. He didn't know anything about track, didn't know anything about coaching, was a hothead, and just had a really bad vibe. I don't remember what happened, but the track season didn't last very long, and we never ran in a meet. I never heard of the "coach" again.

I remember our high school coaches much better. They were typical of coaches I have seen elsewhere - pompous, egocentric, not very bright, favored their star players while ignoring everyone else, and not particularly good teachers. I've seen worse while substitute teaching.

The worst of all was when I had a job driving a school bus in the late 1980s to early '90s. The best money was in taking classes or sports teams on road trips. One Saturday I was assigned to drive the school baseball team to a game against West Aurora, a statewide power. The team lost the game despite a grand slam home run from its star player.

The worst of all was when I had a job driving a school bus in the late 1980s to early '90s. The best money was in taking classes or sports teams on road trips. One Saturday I was assigned to drive the school baseball team to a game against West Aurora, a statewide power. The team lost the game despite a grand slam home run from its star player.Usually when a game ended I would leave with the team as soon as the bus was loaded and everyone on board. Not this time. The coach had me turn of the engine, and proceeded to chew the team out for losing, not for anything specific, just for being losers. He was one of the biggest jerks I have ever come across. I felt like throwing him off the bus. The driver is the authority on the bus, and that was as close as I had come to telling someone to get out. From his tone it was pretty obvious that the coach only cared about himself and his job, and nothing for the players.

Nowadays sports are big business. Professional athletes make millions of dollars a year, and owners make even more, with some exceptions. College sports, technically amateur, have become an embarrassment. Coaches and athletic directors make millions, while players earn no money, at least officially. Schools are continually being caught paying players "under the table," or providing them with cars, clothes, TVs, and even prostitutes.

Here at the University of Wisconsin we have a perfect example. Athletic Director Barry Alvarez earns a salary of $1,000,000 per year. Football coach Bret Bielema's annual take is $2.5 million. Basketball coach Bo Ryan earns $2,111,364.

Here at the University of Wisconsin we have a perfect example. Athletic Director Barry Alvarez earns a salary of $1,000,000 per year. Football coach Bret Bielema's annual take is $2.5 million. Basketball coach Bo Ryan earns $2,111,364.To get a better idea of how big the UW sports program is I took a tour a few days ago of the sports facilities. It's pretty unbelievable. Camp Randall Stadium, where the "Badgers" play football, holds over 80,000 fans.

The Kohl Center, where the basketball and hockey teams play, holds 17,230. In a ranking of profits of major colleges in both football and basketball the football program makes the 22nd highest ($16,621,480), and the basketball program is 42nd ($10,126,893). Both are higher than Southern California's football program, 48th at $8,259,649.

The Kohl Center, where the basketball and hockey teams play, holds 17,230. In a ranking of profits of major colleges in both football and basketball the football program makes the 22nd highest ($16,621,480), and the basketball program is 42nd ($10,126,893). Both are higher than Southern California's football program, 48th at $8,259,649. Most stunning to me among the UW's athletic buildings is the indoor practice facility. It is imposing from the outside, but is even more daunting from the inside, with two underground levels.

Most stunning to me among the UW's athletic buildings is the indoor practice facility. It is imposing from the outside, but is even more daunting from the inside, with two underground levels.  It has an eighty yard football field, a huge weight room, a sports medicine area, team meeting rooms, a tutoring center, and numerous other offices of which I don't know the function.

It has an eighty yard football field, a huge weight room, a sports medicine area, team meeting rooms, a tutoring center, and numerous other offices of which I don't know the function.This is too much. It's too much everywhere. The two schools where I went to graduate school, Southern Illinois University and Northern Illinois University, both decided to go "big time" during my time at each. Money poured in, both from the state and from donors. Now they have expanded stadiums and big athletic budgets. The way college athletics began was to enhance the college experience for the players, making them well-rounded human beings through fair competition.

Now it is big business, the well-roundedness a matter of luck. The student athlete of today is athlete first, student maybe. Some go on to be doctors and lawyers and such, some to be coaches, some to sell insurance, and some go on to alcohol, drugs, crime and an early death. Many, especially football players, end up with serious brain injuries that cause lifetime difficulties. The important thing to the universities is that the athletes bring paying fans through the turnstiles.

The business of college sports has reached a zenith and nadir simultaneously. The money involved is beyond obscene, and now the scandals are rapidly catching up. The Penn State fiasco is the culmination of many years of malfeasance nationwide. If the most reputable sports program in the country covers up for a serial child molester and maybe worse, what, we must wonder, is going on everywhere else?

An even larger question is what is going on in the broader context of business, government, and other institutions. Sunday's 60 Minutes had a segment about how members of Congress from both parties, including the current and previous speakers of the House of Representatives, have been buying stocks based on inside information. These insider trades have yielded millions of dollars in free money. This is nothing new, but it is becoming clear that we have a comprehensively corrupt society.

Given the ongoing Wall Street fraud scandal, the corruption in our Congress, a corporate class that behaves with near-impunity, our increasingly fake mainstream news media, and the breakdown of some of our other major institutions, the larger question is if we are going the way of the Roman Empire. I think we are, but it is also a time of golden opportunity. There has been no other time since the Civil War that our country has been poised for fundamental change. With energy, wisdom, and more than a little good luck, we may be on the brink of a golden age.

_______________________________________________________

Here's an update from Weekend Update.

For a further examination of institutional self-protection, this story from CNN is a good start.

Here's another little update.

Maybe all we need is a little more Bread and Circus. An explanation of the term might help.

We all have dreams of greatness when we are young.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home