Army stories

It was in my senior year in college that I turned against the Vietnam war. I was moving in that direction over several months, but one of my professors suggested to our class that we subscribe to a daily newspaper in order to keep up with the news and issues of the day. The paper I subscribed to was the then Minneapolis Star, now combined with its former competitor the Tribune.

It was in my senior year in college that I turned against the Vietnam war. I was moving in that direction over several months, but one of my professors suggested to our class that we subscribe to a daily newspaper in order to keep up with the news and issues of the day. The paper I subscribed to was the then Minneapolis Star, now combined with its former competitor the Tribune.What gradually dawned on me was that the paper was reporting the war like a sporting event: The front-page headlines every day read "38 to 6," "24 to 3," "45 to 7," or some such. The numbers referred to body counts, and the higher score was always the "enemy." I accepted the false scores as true, but came to the realization that I was being "pitched," that the way the war was presented was intended to sell the war.

A servile media is nothing new. It was new to me, though, and I have had a skeptical eye towards "news" of any kind ever since. I only subscribed to the newspaper for a few months, and then I graduated. The reigning Vice President of the United States, Hubert H. Humphrey, spoke at my graduation. The ceremony was picketed, not because I was graduating, but because of the war. The most anyone among the graduates did in the form of protest at the small Catholic college I went to was to turn their noses up when they went past him. I wasn’t one of them.

Graduation meant the end of my draft deferment, so the next step in life for me was military service. I wasn’t against the war enough to resist the draft, and my father was from the World War II generation; he attached a stigma to being drafted. There was a short family history of being Army officers, so I started going through the process of signing up for Officers Candidate School (OCS). My older brother had already enlisted for OCS, and was told by the recruiters that he would get a branch transfer out of the Infantry upon graduation. They told me the same thing, and I almost took the plunge, but my brother warned me that they had been lying in order to meet their recruiting quotas. So I backed off.

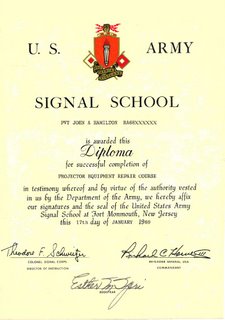

Eventually I got my draft notice, and my father was giving me grief about not enlisting, so I checked out my options. Everything in the book of specialties that looked interesting was closed: computer programmer, combat journalist (That was my Ernie Pyle fantasy, not a very smart one.), mechanic, small arms repair, even cook. One day, as I was thumbing through the book, I read the job title "Projector repair." It seemed so ridiculous to me that you could enlist to be a projector repairman that I said to myself, "That’s me!" I signed up, beat being drafted by days, and off to Basic Training I went, to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri.

Eventually I got my draft notice, and my father was giving me grief about not enlisting, so I checked out my options. Everything in the book of specialties that looked interesting was closed: computer programmer, combat journalist (That was my Ernie Pyle fantasy, not a very smart one.), mechanic, small arms repair, even cook. One day, as I was thumbing through the book, I read the job title "Projector repair." It seemed so ridiculous to me that you could enlist to be a projector repairman that I said to myself, "That’s me!" I signed up, beat being drafted by days, and off to Basic Training I went, to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri.I may have been headed for a school for pikers, but Basic Training is the same for everyone. Very hard. I went into the Army with the attitude that I would cross every bridge when I came to it, and, having been a Boy Scout and a hunter, as well as a bench-warming football player and mile runner in track, I figured I could handle what came my way. I also had seen a number of World War II goof-off movies with people like Dean Martin, Ernie Kovacs and James Garner, and had visions of such a time for myself. My dad had told me many stories about goofing off in World War II in the various places he was stationed, mainly Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, and the Philippines. Looking back on it, it was his attitude that influenced me the most, and enabled me to approach the experience with a sense of lightness.

I actually kind of liked basic training. I enjoyed marching in step, especially turning movements – my favorite was "To the rear...march!" - singing the cadence songs like "Around her hair she wore a yellow ribbon; she wore it in the springtime, and in the month of May. And if you asked her why the heck she wore it, she wore it for her trainee, so far, far away!" Etcetera. We also did call and answer to such ditties as "Your mother was home when you left! (You’re right!) Your girlfriend was home when you left! (You’re right!) Jodie was home when you left! (You’re right!)" Jodie was a fictitious character who was stealing your girlfriend or wife while you were gone. It didn’t mean anything to me, because I had neither girlfriend nor wife. It did mean something to many of my fellow trainees, and it turned out that a goodly number of them were indeed being cheated on. The cadence calls were the Army’s way of preparing them for the possibility. We did call-and-answer to such cheerful lines as "If I die in Vietnam, box me up and ship me home! Yo left, yo left; yo left, right, left!" (A variation on this was "If I die in Vietnam, Jodie's got my girl and gone!") Another favorite was "Viet-na-a-a-am, Viet-na-a-a-am! Late at night while you’re sleepin’ Charlie Cong comes a creepin’ all arou-ou-ou-ou-ou-oun-nd!" This was done to the tune of the Rhythm and Blues hit "Poison Ivy," by the Coasters. Click here to have a listen. The name "Charlie" was used because the National Liberation Front (NLF), which was the guerrilla movement in "South Vietnam" that fought against the "Americans," was known as the Vietcong, or "VC." In the NATO phonetic alphabet used by the military, VC translates to "Victor Charlie."

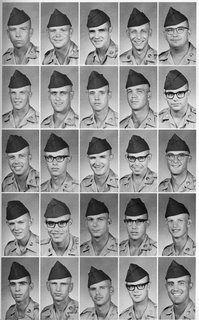

I actually kind of liked basic training. I enjoyed marching in step, especially turning movements – my favorite was "To the rear...march!" - singing the cadence songs like "Around her hair she wore a yellow ribbon; she wore it in the springtime, and in the month of May. And if you asked her why the heck she wore it, she wore it for her trainee, so far, far away!" Etcetera. We also did call and answer to such ditties as "Your mother was home when you left! (You’re right!) Your girlfriend was home when you left! (You’re right!) Jodie was home when you left! (You’re right!)" Jodie was a fictitious character who was stealing your girlfriend or wife while you were gone. It didn’t mean anything to me, because I had neither girlfriend nor wife. It did mean something to many of my fellow trainees, and it turned out that a goodly number of them were indeed being cheated on. The cadence calls were the Army’s way of preparing them for the possibility. We did call-and-answer to such cheerful lines as "If I die in Vietnam, box me up and ship me home! Yo left, yo left; yo left, right, left!" (A variation on this was "If I die in Vietnam, Jodie's got my girl and gone!") Another favorite was "Viet-na-a-a-am, Viet-na-a-a-am! Late at night while you’re sleepin’ Charlie Cong comes a creepin’ all arou-ou-ou-ou-ou-oun-nd!" This was done to the tune of the Rhythm and Blues hit "Poison Ivy," by the Coasters. Click here to have a listen. The name "Charlie" was used because the National Liberation Front (NLF), which was the guerrilla movement in "South Vietnam" that fought against the "Americans," was known as the Vietcong, or "VC." In the NATO phonetic alphabet used by the military, VC translates to "Victor Charlie." Most of the things in basic training made sense to me, and I took them as personal tests, not so much of "manhood," but just for me, to see what I could do. We had to crawl through the "Infiltration course," a sand field that had blank mines in it, with live machine gun fire overhead. Every fifth round was a tracer, so we knew it was real. They told us it would be about chest high, and I had a very simple approach: Get through this, don’t stand up. Some guys, typically the loudmouths of the unit, froze in fear, and couldn’t climb out of the trench we were in when ordered to get out and crawl. I figured "Better to find out now, than when you’re in a combat situation." Time and again, throughout the 8 weeks of basic, the hot shots, drugstore cowboys, blowhards, and braggarts were the ones who caved when the pressure was on. (In the picture at right, one guy went crazy, then AWOL. One guy was a blowhard. I'm in the exact middle. The guy above me to the right, who looks like a tough guy, was. He played football at Tulane, was a big star, the team captain in 1965, a good guy. I hope they all escaped danger, but I know some of them didn't. I never saw or heard from any of them again.).

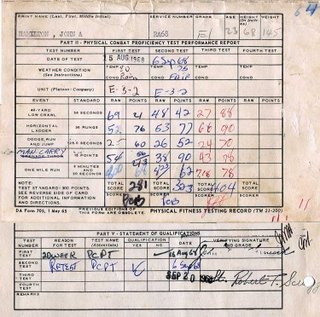

Most of the things in basic training made sense to me, and I took them as personal tests, not so much of "manhood," but just for me, to see what I could do. We had to crawl through the "Infiltration course," a sand field that had blank mines in it, with live machine gun fire overhead. Every fifth round was a tracer, so we knew it was real. They told us it would be about chest high, and I had a very simple approach: Get through this, don’t stand up. Some guys, typically the loudmouths of the unit, froze in fear, and couldn’t climb out of the trench we were in when ordered to get out and crawl. I figured "Better to find out now, than when you’re in a combat situation." Time and again, throughout the 8 weeks of basic, the hot shots, drugstore cowboys, blowhards, and braggarts were the ones who caved when the pressure was on. (In the picture at right, one guy went crazy, then AWOL. One guy was a blowhard. I'm in the exact middle. The guy above me to the right, who looks like a tough guy, was. He played football at Tulane, was a big star, the team captain in 1965, a good guy. I hope they all escaped danger, but I know some of them didn't. I never saw or heard from any of them again.). As well as marching, I also enjoyed "facing movements" – left face, right face, and about face; bayonet training, and the rifle range. I enjoyed doing the Manual of arms . I even liked "PT" – Physical Training – pushups, deep knee bends, etc., and especially liked hand-walking the horizontal ladder.

As well as marching, I also enjoyed "facing movements" – left face, right face, and about face; bayonet training, and the rifle range. I enjoyed doing the Manual of arms . I even liked "PT" – Physical Training – pushups, deep knee bends, etc., and especially liked hand-walking the horizontal ladder. It wasn’t all work, either, and there were some uproariously funny incidents, too long to describe here. Before I knew it, the eight weeks was over, I got my first and only service ribbon – the National Defense Service Medal, a Sharpshooter medal for rifle and grenade, a promotion to Private E-2, and I was off to projector repair school, at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey.

It wasn’t all work, either, and there were some uproariously funny incidents, too long to describe here. Before I knew it, the eight weeks was over, I got my first and only service ribbon – the National Defense Service Medal, a Sharpshooter medal for rifle and grenade, a promotion to Private E-2, and I was off to projector repair school, at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey.Projector Repair school was enjoyable, interesting, and challenging. It wasn’t just about movie projectors, but also covered slide, overhead, and opaque projectors, as well as amplifiers, microphones, reel-to-reel tape recorders, and speaker technology. It was a full-fledged electronics school, and I was very impressed with the quality of Army schooling.

My class consisted of about 12 new enlistees and two Marines - each for different reasons living examples of why the Marine Corps should be abolished. There were many other training programs at Ft. Monmouth, including radar repair, microwave repair, camera repair, and even TV repair. In other areas of the base there were schools I knew nothing about, and didn't particularly care.

The base was also more fun than Ft. Leonard Wood. There was more of a concentration of anti-war GIs at Ft. Monmouth than I had seen in basic training, and they were much more open about it. A group of us grew Hitler mustaches as a way of looking ridiculous in our uniforms, and I was the last one to shave mine off. I had to report to a lieutenant for missing KP (kitchen police), and it was a comical scene, he being almost as big a goof-off as I was. I had a number of priceless moments during my 12 weeks at Ft. Monmouth, and they were a good preparation for what was to come.

After graduation from projector repair school I was sent to Germany, along with three of my classmates. The unit I was sent to did not have authorization for a projector repairman, so they asked me "Can you type?" Thus began a new Army career. I didn’t repair a single projector in my entire time in the Army.

The unit I was assigned to, the 66th Maintenance Battalion, was located in Kaiserslautern, Germany, a "GI town." There was a soldier for every three Germans, I was told. Kaiserslautern is in southwest Germany, about 30 miles from the French border. It was bombed pretty heavily in World War II, and there were still ruins in various parts of the town. One of my best friends, the "Happy Hawaiian," told me that his father had bombed Kaiserslautern.

The unit I was assigned to, the 66th Maintenance Battalion, was located in Kaiserslautern, Germany, a "GI town." There was a soldier for every three Germans, I was told. Kaiserslautern is in southwest Germany, about 30 miles from the French border. It was bombed pretty heavily in World War II, and there were still ruins in various parts of the town. One of my best friends, the "Happy Hawaiian," told me that his father had bombed Kaiserslautern."K-town," as it was called, was a pit. Because there were so many GIs, the economy of the town was built around entertainment for the soldiers: drinking, prostitution, drinking, and prostitution. Prostitution is legal in Germany, and the practitioners could be seen at several roadside areas in town (It is worth mentioning that prostitution is also legal in the "USA," particularly in the fields of business, government, and journalism). Antiwar GIs found each other out with relative ease, and we managed to find alternative forms of entertainment, consistent with the cultural ferment of the times.

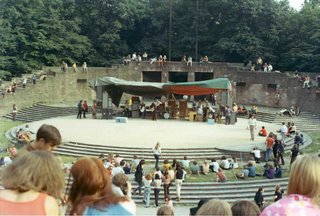

The area around Kaiserslautern had beautiful mountains and forests, and we would explore them on weekends and holidays. We also went on Service Club tours - of the Rhine River, Baden-Baden, Würzburg, Karlsruhe, and other festive and picturesque areas. One of my favorite memories is of a group of us getting "confused and disoriented" in a maze of hedges at the Frankfurt Zoo. Another time about ten of us climbed one of the mountains around Kaiserslautern, got "confused and disoriented," then pried a huge boulder loose, and jumped up and down in glee as we watched it bounce down the mountain. Luckily, there was no one in the woods below. And then there was the legendary "Club 65" in Frankfurt, a rock club frequented by GIs who didn't necessarily imbibe alcohol. Whoever went there would remember forever the huge Jimi Hendrix poster behind the stage.

The area around Kaiserslautern had beautiful mountains and forests, and we would explore them on weekends and holidays. We also went on Service Club tours - of the Rhine River, Baden-Baden, Würzburg, Karlsruhe, and other festive and picturesque areas. One of my favorite memories is of a group of us getting "confused and disoriented" in a maze of hedges at the Frankfurt Zoo. Another time about ten of us climbed one of the mountains around Kaiserslautern, got "confused and disoriented," then pried a huge boulder loose, and jumped up and down in glee as we watched it bounce down the mountain. Luckily, there was no one in the woods below. And then there was the legendary "Club 65" in Frankfurt, a rock club frequented by GIs who didn't necessarily imbibe alcohol. Whoever went there would remember forever the huge Jimi Hendrix poster behind the stage.The unit I was in was also a pit: low-level, sleazy interactions, harassment, corruption (The officers pilfered the KP fund.), rancid food (The mess sergeant sold the steaks we were supposed to have.), and a lot of makework: inspections, "motor-staples" - a tedious round of vehicle inspections, and the catch-all, "police-call" – picking up bits of trash on the ground. We paid $5.00 per month for civilian KPs - dishwashers - and they were all semi-retired "Strasse queens" - streetwalkers. They looked like Don Martin drawings from Mad Magazine.

A dog walked into our "mess hall" one day, and someone threw him a piece of the green beef we had been served. He picked it up, took a few chews, then spit it out and walked out the door, insulted. One of my friends piled his plate one day with the disgusting food we were eating, and we asked him what he was doing. He had an ulcer, and as he piled the food in his mouth, he said, "I'm gettin' out of this army, and I don't care what it takes." He ended up serving his entire enlistment, but at least got transferred out of K-town (to Mannheim).

I hated the place, and had a monthly crisis where I contemplated desertion. Some guys did desert. Usually it was done while home on leave. It was easy to go to Canada in those days, and they welcomed deserters. The European option was Sweden, a more difficult choice because of the language barrier and the distance from home. If you went to Sweden, you were really deserting – family, home, everything familiar.

As destiny would have it, after nine months in Kaiserslautern I found myself in Heidelberg, working in the conference room of the Commander in Chief, US Army Europe (CINCUSAREUR). Every year, according to legend, the Command Building was given a budget of $67,000 for an improvement project. That year, 1969, the Army generals felt upstaged by the quality of the conference room the Air Force had in Wiesbaden, and decided to remodel their conference room, and equip it with a state-of-the-art projection booth with all the latest sound and projection technology available. They really went all-out, and bought things well-beyond what they would ever use.

As destiny would have it, after nine months in Kaiserslautern I found myself in Heidelberg, working in the conference room of the Commander in Chief, US Army Europe (CINCUSAREUR). Every year, according to legend, the Command Building was given a budget of $67,000 for an improvement project. That year, 1969, the Army generals felt upstaged by the quality of the conference room the Air Force had in Wiesbaden, and decided to remodel their conference room, and equip it with a state-of-the-art projection booth with all the latest sound and projection technology available. They really went all-out, and bought things well-beyond what they would ever use. To staff the projection booth, the Personnel personnel were ordered to find the most suitable Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) for running the equipment, and scour USAREUR for anyone with that MOS. As it turned out, the closest MOS was 41foxtrot (41F20), my MOS. I was "levied" to Heidelberg, the city of "The Student Prince", a beautiful, cultured city that had a castle, many historic buildings and other structures, and most important of all, was not Kaiserslautern. (Heidelberg also had "Club Storyville," a cavernous jazz-rock-folk club that had two underground levels. Fortuitously, I rented a place off-post that was a block away.)

To staff the projection booth, the Personnel personnel were ordered to find the most suitable Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) for running the equipment, and scour USAREUR for anyone with that MOS. As it turned out, the closest MOS was 41foxtrot (41F20), my MOS. I was "levied" to Heidelberg, the city of "The Student Prince", a beautiful, cultured city that had a castle, many historic buildings and other structures, and most important of all, was not Kaiserslautern. (Heidelberg also had "Club Storyville," a cavernous jazz-rock-folk club that had two underground levels. Fortuitously, I rented a place off-post that was a block away.)I only had the job for three months. It required a Top Secret security clearance, so I was given an interim clearance while my background was being searched. After three months they decided they had too many projector repairmen, and someone had to go. Since my security clearance hadn’t been finalized, I was the prime candidate, and was sent over to "SMC," the Staff Message Center. I was given a job stamping messages with the appropriate security designation, like "Confidential," "Secret," "Top Secret," and my favorite, "Unclassified EFTO," which meant encrypted for transmittal only. Most of the messages had this designation, so I got to stamp "Unclassified EFTO" to my heart’s delight.

I didn’t last long in this job either, because I had a tendency to read the messages, and got behind on my stamping. This place really cranked out the messages. When they transcribed them to be sent to the appropriate office or unit, the messages were printed in numerous copies, so a few printing machines were heavily involved in the process. The poor guy who ran the machines worked himself to exhaustion. One of the curious things about the printing was that everything that went to the CinC, General Polk, had to be on pink paper to accommodate his failing eyesight. It added a Washingtonian touch to his character.

My next stop was the 503d Transportation Company, still in Heidelberg, but at Patton Barracks instead of the Headquarters at Campbell Barracks. There I stayed until I was in a car wreck in November of 1970, and was put in charge of a drivers school. I wrote a bit about my time in the 503d in a previous post, "Similarities."

My next stop was the 503d Transportation Company, still in Heidelberg, but at Patton Barracks instead of the Headquarters at Campbell Barracks. There I stayed until I was in a car wreck in November of 1970, and was put in charge of a drivers school. I wrote a bit about my time in the 503d in a previous post, "Similarities." While supervising the drivers school I was appointed to a new position as coordinator of the "Human Relations Office," a weak attempt at addressing morale problems and drug abuse. One of the few things I actually did in this job was to meet with the Commanding General of the Seventh Army, Major General William R. Kraft, Jr. He was really impressive - a tall, very intelligent, decent and friendly man, whom I expected to some day become Supreme Allied Commander of NATO or Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He probably was too good for both jobs, since it seems his last position was Chief of Staff at USAREUR Headquarters. General Kraft actually listened to what I had to say, and was not the least bit arrogant. He also was tolerant of my lack of proper protocol, a lifelong habit.

While supervising the drivers school I was appointed to a new position as coordinator of the "Human Relations Office," a weak attempt at addressing morale problems and drug abuse. One of the few things I actually did in this job was to meet with the Commanding General of the Seventh Army, Major General William R. Kraft, Jr. He was really impressive - a tall, very intelligent, decent and friendly man, whom I expected to some day become Supreme Allied Commander of NATO or Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. He probably was too good for both jobs, since it seems his last position was Chief of Staff at USAREUR Headquarters. General Kraft actually listened to what I had to say, and was not the least bit arrogant. He also was tolerant of my lack of proper protocol, a lifelong habit.This was a bit of a lengthy introduction, but what I really want to write about is Army generals. Before I was sent to Heidelberg I thought all generals were evil masterminds of war, unfeeling tyrants who wantonly sent men to their deaths. It was an easy, though ignorant view to have, since the dominant figure in the Army at that time was General William Westmoreland, the Chief of Staff, and former commanding general of the U.S. operations in Vietnam. He was an unsmiling, Boris Karloff-looking personage, and what little energy we gave him was contempt.

The generals, as it turned out, were anything but the stereotype I had of them. The Commander in Chief, James H. Polk, was a four-star general, and a soft-spoken, grandfatherly character. The other generals - the Chief of Staff, and deputy chiefs of staff for personnel, operations, intelligence, logistics, the Engineer, the Surgeon, and the commanding generals for the different combat divisions – Infantry, Armor (tanks), and Artillery (cannons) – came in all shapes and sizes. Some were red-faced alcoholics, some were serious and dignified, some were arrogant and self-absorbed, and some were warm and friendly. One of my favorites was a general named Clapsaddle. It was a name right out of "Catch-22." He was a two or three star general, and looked like a Rockefeller, tall and lean, and had a kind of New England look about him, and he was kind and friendly. I think he was DCSPER, which meant Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, but he could just as easily have been DCSLOG, DCSOPS, or DCSINTEL.

What makes all of these experiences pertinent to our present circumstance is the growing chorus of retired generals who are speaking out against the Bush crime family's conduct of the Iraq war, and by implication of its plans for fomenting attacks on other countries, starting with Iran. Suffice it to say that generals are human beings, and they are starting to show it in their recognition of the futility of the Iraq war, and their disgust with the sociopaths who cooked it up. They also realize that the gang of criminals running this country are likely to get us into a nuclear weapons grade world war if they aren't stopped.

To help explain the dissent of the generals, much acclaim is given to the book "Dereliction of Duty," by H.R. McMaster. The book describes the folly of the Vietnam war, with politicians, chiefly President Lyndon B. Johnson, cooking up pretexts for the war, and then directing the waging of it in an inept manner. McMaster faults the upper echelons of the military, the generals and admirals, for submitting in such feeble manner to the incompetent and criminal schemes of foolhardy politicians.

This would include the generals that I worked for. It was said during the Vietnam war that career officers welcomed it because they could go there and "get their tickets punched" - get a war experience on their records, get some medals (earned or not), and move up the ladder of "success."

Another book that is getting a lot of mention is the novel "Once an Eagle," by Anton Myrer, written in 1968. In it Myrer described the career paths of two Army officers. One is the classic warrior, rising through the ranks by commanding troops, while the other is a scheming bureaucrat in the Pentagon.

These factors add a lot of complexity to an already complex situation, but as always, things can be sifted down to their basic elements. The government of the United States of America has been seized by a criminal gang. The gang is on a path for taking power over the entire planet. This plan is absolutely guaranteed to fail, for a number of reasons, presented in earlier postings in numerous ways.

The upper echelons of the military have begun to realize that they are being played for chumps, expected to passively go along with the imperial schemes of the Bush crime family, and to send the soldiers they command to their deaths for an endless criminal operation. This is a complete inversion of the duty, honor, and country that they were taught at West Point, Annapolis, Colorado Springs, College Station, Lexington, Charleston, and at colleges and universities throughout the nation. I know from experience that generals, as a class, are not fiends. Individually, that may be another story, as Boykin and Miller suggest. When they are successful, they can go either in the direction of Eisenhower, or in those of LeMay or MacArthur.

It's an interesting sideshow, the revolt of the generals. Supposedly, "SECDEF" Rumsfeld thinks it will die out, but it won't. The long arm of the law is closing in on the Bush crime family. U.S. Attorney Patrick Fitzgerald is likely to announce further indictments of members of the Bush crime family any day now. The connections between the criminal activities of lobbyist Jack Abramoff and the Bush gang are likely to become public knowledge any day now. The Iraq war is not likely to become an instant success. And the criminal plan for bombing Iran is likely to become exposed, very likely because of whistle-blowing by the intelligence agencies and/or the military. At some point international law will get involved in the mix.

Trumping all of these factors, though, is the asymptotic trajectory of our civilization towards its own ruin. I say asymptotic because it is a point we are approaching, but won't reach. I'm an optimist. Being an optimist, I contend that we will indeed make the changes necessary to save our civilization. As long as the Bush crime family is allowed to pursue its evil quest for world domination, we are doomed. Therefore, exit left the Bush crime family. Their hour of strutting and fretting upon the stage is just about up. They will soon be heard no more.

____________________________________________

Some additional Army stories can be read here, here, and here.

Here's an example of how serving in the Army changed during the "Vietnam" war.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home